Yellow Dog Productions

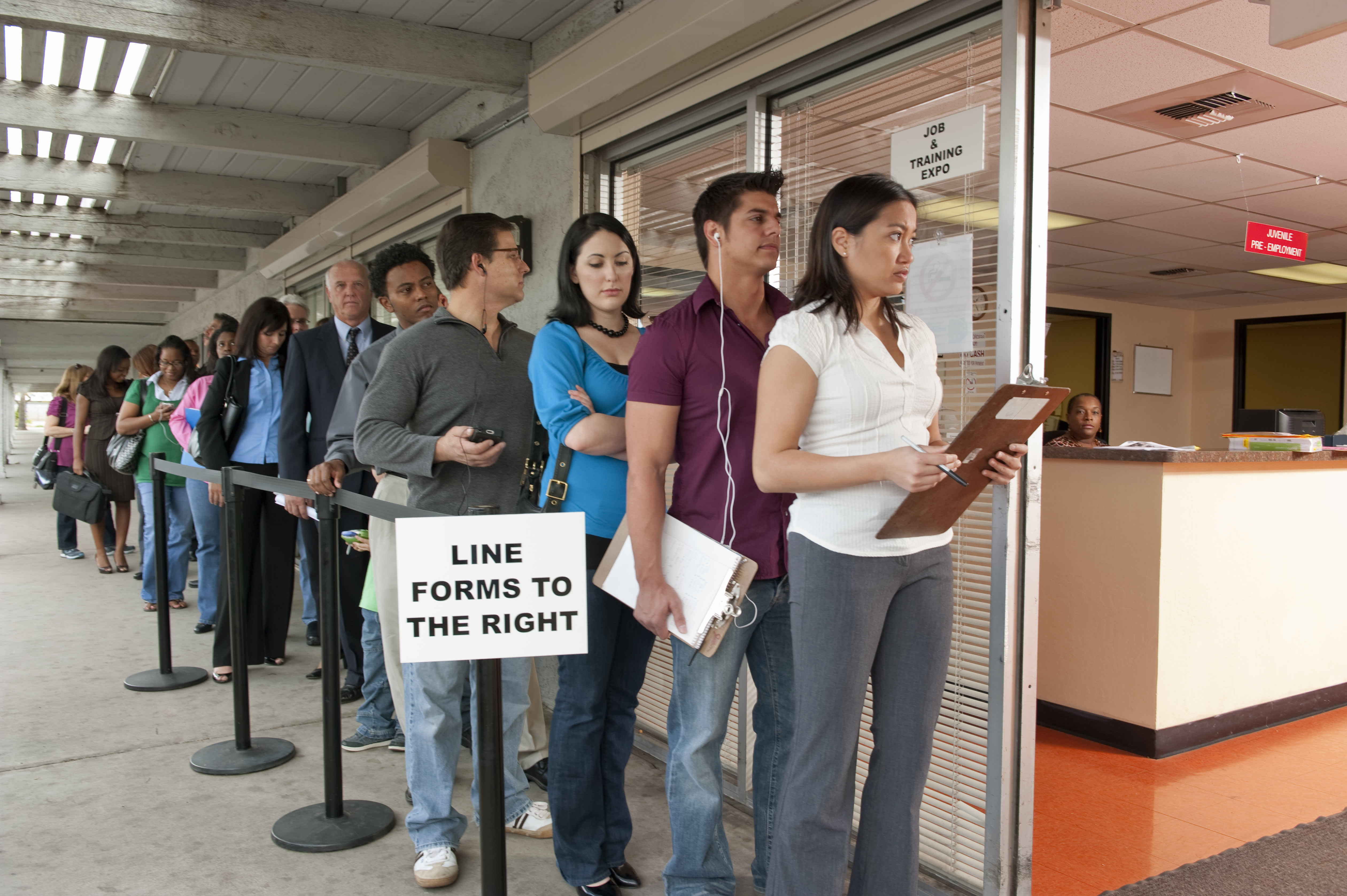

The economic fallout from the coronavirus is driving more Americans to seek unemployment benefits.

However, the nation’s main financial backstop for laid-off workers is deficient — which could leave many Americans, especially gig workers, in a precarious situation, according to some experts.

The $100 billion aid package President Trump signed into law on Wednesday, which contains unemployment provisions, doesn’t address the core issues, experts said. However, the law may alleviate some of the financial burdens shouldered by the states relative to unemployment.

“The system is not working well,” said Stephen Wandner, a labor economist with the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research and senior fellow at the National Academy of Social Insurance.

Lawmakers established the unemployment insurance program in 1935 under the Social Security Act.

At a micro level, unemployment insurance provides temporary income support for workers who lose their jobs. At a macro level, the program — which is administered by the states — helps prop up the U.S. economy.

In January, the program paid $385 in average weekly benefits, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The coronavirus, or COVID-19, is inflicting severe economic damage, shutting down entire industries and forcing businesses to cut their workforce as the pandemic worsens.

First-time claims for unemployment increased 33% last week, to 281,000, according to figures released Thursday by the Labor Department. The increase is “clearly attributable to impacts from the COVID-19 virus,” the agency said.

The numbers will likely skyrocket in the coming weeks, economists believe, especially since the latest national figures don’t encapsulate data in the wake of bar, restaurant, gym and other business closures ordered by some state officials.

Unemployment could jump to 20% — about double its peak during the Great Recession — absent financial intervention, Treasury Secretary Stephen Mnuchin told Republican lawmakers this week.

There are states that don’t want to pay benefits. And they do a good job at not paying.

Stephen Wandner

labor economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

A spike of that magnitude would be especially dramatic since unemployment in the U.S. before the coronavirus pandemic had been near 50-year lows.

More than 14 million Americans collected unemployment at the peak of the Great Recession.

Today’s unemployment insurance program won’t provide an adequate financial backstop for many Americans, who could see broad variations in treatment depending on their state, experts said.

For one, gig workers — who represent a greater share of the workforce than in the past — don’t qualify for unemployment benefits, said Wandner, a former actuary at the Department of Labor. Uber, Lyft and other companies employing gig workers don’t pay taxes that fund states’ unemployment insurance trust funds.

“That’s a big problem,” said Wandner, especially since the coronavirus’ economic hit seems particularly acute in service industries replete with gig workers.

In another twist, part-time workers who lose their jobs also can’t collect benefits in many states unless they can prove they are looking for full-time work, experts said.

Insufficient tax funding has also led many states — mostly in the South — to reduce the maximum duration and amount of unemployment payments, and make it more difficult to apply and be eligible for benefits, Wandner said.

Roughly a decade ago, around the time of the Great Recession, states generally offered up to 26 weeks — about 6½ months — of unemployment.

Now, nine states are less generous. Some, like Florida and North Carolina, offer less than half that amount, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

By comparison, rules put in place during the 2008 financial crisis allowed most workers to collect up to 99 weeks of unemployment, according to Chad Stone, chief economist at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

At a national level, workers collecting unemployment replace roughly a third of their prior weekly wages. That’s a reduction from around 37% a few decades ago, according to a report published in January by the Upjohn Institute.

The share of unemployed workers collecting unemployment checks has also dropped nationally, to about 30% today from more than 40% a decade ago, according to the Upjohn Institute. In North Carolina, just 11% of unemployed workers receive benefits, the lowest share of any state.

“There are states that don’t want to pay benefits,” Wandner said. “And they do a good job at not paying.”

Of course, state and federal officials could potentially bolster the unemployment insurance program in coming weeks in any upcoming financial-relief packages Congress passes, experts said.

But the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which the president signed into law on Mar. 18, doesn’t do much to alleviate the program’s flaws, they said.

“People think that bill has done a lot of important things, when it’s a drop in the bucket,” Stone said.

Perhaps the law’s biggest contribution relative to unemployment is additional administrative funding for states, which could help states process claims more quickly if there’s a surge, experts said.

Under the new law, it appears the federal government would assume more financial responsibility for an “emergency benefits” mechanism that’s currently in place, Stone said. That could give certain workers up to 20 additional weeks of unemployment in a recessionary environment.

However, that improvement wouldn’t help overcome those other hurdles for a large swath of the workforce.

“In the recession we’re likely to be in now, much more needs to be done,” Stone said.